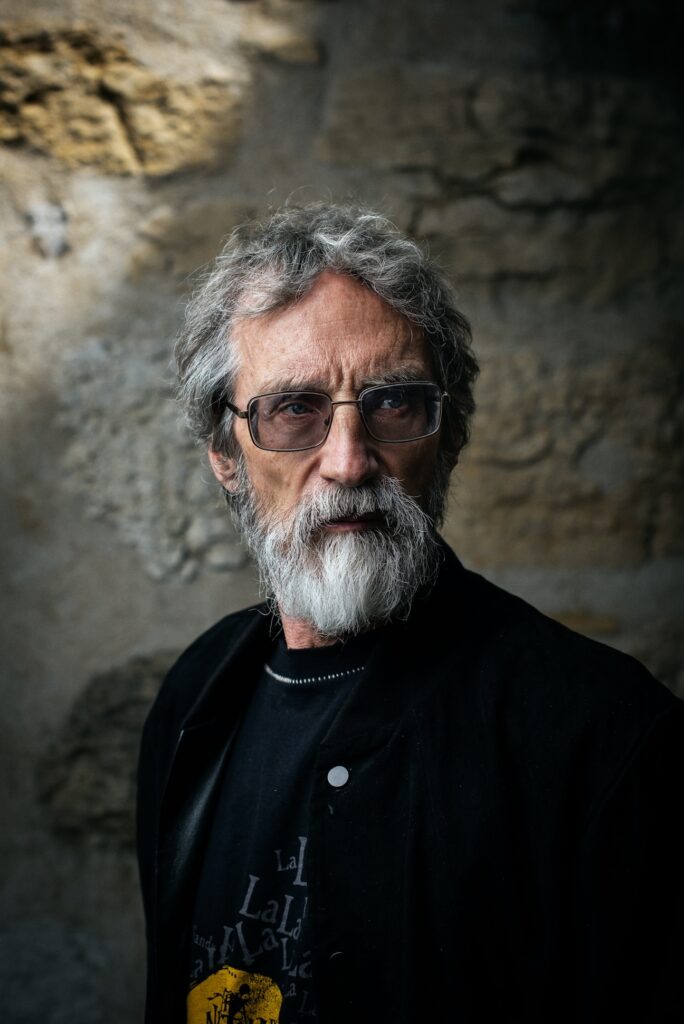

“When I was in New Zealand doing concept design for Peter Jackson‘s The Hobbit, there was one image that just wouldn’t work, and I couldn’t figure out why. Then I realised that because the pieces were done digitally, I couldn’t hear the brush strokes on the paper. How a single stroke slowly becomes drier and drier,” says veteran illustrator John Howe.

The physicality of creating art is clearly important to Howe. He describes how he guides adults, who haven’t drawn since childhood, to change the way they hold their pencil.

“It is indeed a physiological phenomenon. When using a pencil, we have a writing mode and a drawing mode. Writing is mainly done with our fingers, and it’s drilled into our heads at school. By changing the way we hold our pencil, we can try to break free from our school years and strive for the drawing mode.”

“I try to create my artworks without leaning on the table or on the paper in order to relinquish as much control as possible.”

Born in 1957 in Canada, Howe moved to France to study after high school. Seeing the Strasbourg Cathedral was an experience that altered the course of his life.

“They really do exist! So it’s all true,” Howe recalls thinking.

“As there are no truly old buildings in Canada, the history of architecture was utterly theoretical for me. It was the very first Gothic building I ever saw with my own eyes.”

Howe became so enthusiastic about the cathedral that he managed to convince them to give him a master key.

“I went everywhere – and I mean absolutely everywhere.”

Howe’s picture book Cathedral (published in French 1995 and in English 2024), which depicts the site all the way up to its towering spire, bears witness to this.

Howe has carved his career path through medievalism, mythology and fantasy. Primarily as an illustrator, but also as a historian and even co-author of the non-fiction book The Medieval Soldier (1995).

“I think the Middle Ages must have the biggest fan base of all,” Howe ponders.

“Archaeologists and historians do the serious work. Medievalists, in turn, enter that sphere to spend their free time. Artists are unchained spearmen, the original freelancers, who can go either way.”

Howe bases his illustrations of myth and fantasy on real cultural history. “We have thousands of years worth of art, architecture and design. Using it as the basis for illustration lends the image more credibility and helps the reader step into its world.”

“The source materials are a treasure trove, although they can also be a trap that ties you up,” Howe cautions.

He emphasises that simply cutting and pasting a bunch of details together isn’t a great approach. He considers it a common mistake, particularly in the realm of concept design.

“The illustrator must digest what they see and strive to create synthesis. The aim of fantasy art should be to find the intersection between the collective experience of the audience and the personal experience of the artist.”

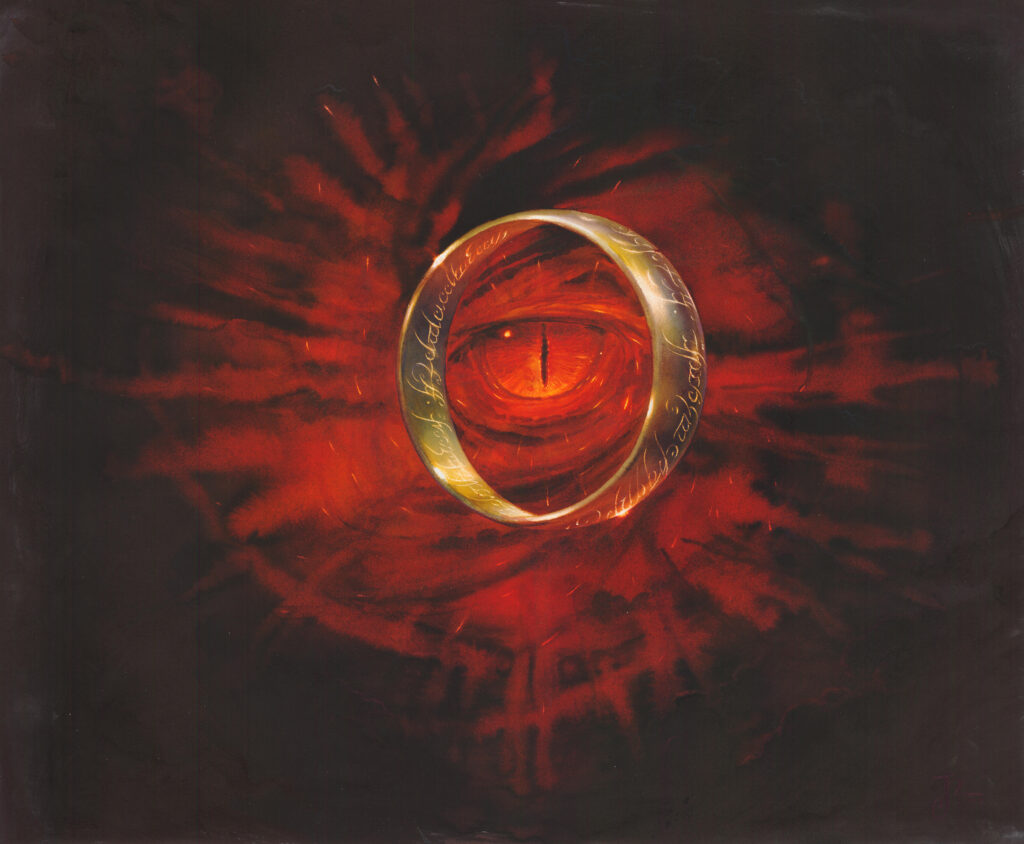

During his career, Howe has illustrated works such as Beowulf and tales of King Arthur as well as fantasy novels by Robin Hobb and George R.R. Martin. He is, however, best known as the illustrator of J.R.R. Tolkien‘s works. He first worked on the books and calendars, and later on the films directed by Peter Jackson, for which he served as lead concept artist alongside Alan Lee.

Tolkienists are known for being ardent purists when it comes to the original texts. That might scare many illustrators away from the subject, but Howe doesn’t see it as an insurmountable obstacle.

“Tolkien’s fans are dedicated, unyielding and encyclopaedic in their knowledge – but anything left unsaid in the texts is fair game,” he says.

“It would hardly be interesting to illustrate only what the text describes, and it isn’t appropriate to veer off from what the source details. But otherwise, one is quite free.”

In Howe’s view, Tolkien tends to focus on describing emotional states rather than external details. There are dragons in the story, for example, but not much thought is given to how they create fire.

“Tolkien remains in the epic realm. He doesn’t do science. Middle-earth is initially flat and then transforms into a sphere. Quite the natural phenomenon!” Howe notes with a hint of irony.

“How can you visualise it all? There are clear indications in some places: Rohan clearly draws from the Anglo-Saxon era and Hobbiton from the Victorian period.”

Howe views Tolkien’s world as a mosaic made up of such contradictory elements.

“But do they all fit together? Apparently! Many other fantasy worlds are more coherent. George R.R. Martin’s books, for example, are more clearly set in the Middle Ages. I believe Tolkien wrote instinctively and was carried away by the flow of his own creativity. It resulted in a world that accommodates a diverse array of things.”

Howe doesn’t consider his illustrations as definitive interpretations of the text.

“What did John Tenniel capture in his Alice in Wonderland illustrations? Many others have created more beautiful images, but none of them have left such a lasting impression,” wonders Howe.

“Gallen-Kallela, whom I greatly admire, managed to transform Kalevala into a graphic form.”

Howe talks about the parallax between the writer and the illustrator. They are like two eyes viewing the same image from slightly different angles. When combined successfully, they create a three-dimensional experience for the reader.

But since the same text can be illustrated time and again, Howe feels that the text itself is more lasting than its illustrations.

“Illustrations come and go, texts stay.”

Howe visited Finland last summer when an extensive exhibition of his works was displayed at Tampere Hall. Seeing his own works in this manner was new for him.

“I don’t look back. I’m not interested in the works I’ve done in the past, as I can no longer change them. I’m as much of a tourist in front of them as anyone, since I never view them in this way.”

Despite his forward-looking attitude, Howe has kept most of his originals, making large exhibitions like this possible.

“In illustration exhibitions, artworks are taken out of their original context. Seeing them thus takes you on a tour inside the artist’s mind. Tour de raison, as the French say.”

“For me, of course, it’s above all an opportunity to encounter the audience of my work.”

Howe is more than happy to explore the works of other artists in museums, however. He again returns to the physicality of art:

“Standing in front of a work of art allows you to interact with a real, tangible object. No Google can replace that experience.”

According to Howe, works of art can transcend temporality. The emotions and ideas that the author has poured into the piece in their own time can be experienced at any other time as well.

“Through works of art, even an empty museum is full of people.”

In this respect, Howe doesn’t believe that AI can erase the true essence of creating art.

“It is the apple hanging from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, of course, and will surely flood the world. My works have already been used to train it.”

“But it’s seeing art-making only in terms of results, while the most important aspect is the creative process itself. Creative self-expression can be life-changing for its author. It has the potential to be life-changing for the recipient as well, since no image is complete without you, the viewer.”

Noki-Helmanen / Tampere Hall

This article was published in Kuvittaja Magazine 4/24.