Have you ever wondered how herrings might talk amongst each other?

Polish illustrator Gosia Herba certainly has. She’s currently working on two books, one of which is a non-fiction book about fish, commissioned by the London-based publishing house Wide-Eyed Editions.

Today, on the drawing table in Herba’s study, herrings are recording music by farting.

“I know it sounds ridiculous, but I’m having a blast,” she says on the phone.

Herrings indeed communicate with each other through underwater sounds produced by gas released from their bodies. In autumn last year, for example, the Swedish Navy reportedly launched a major search operation after mistaking a school of farting herrings for a Russian submarine.

Who knows what the herrings were saying. Perhaps they had band practice, like in the book Herba’s illustrating.

Herba lives in Wroclaw, southwestern Poland, and has a small study in her apartment. In addition to the book on fish, she’s also working on the second part of a series about vampire frogs, and more books are planned for next year.

She’s thus very busy, and that’s a good thing.

“It’s a relief not to have to worry about finding enough work, but it’s also a shame that I have to turn down some projects due to lack of time.”

Herba describes how she used to be a workaholic in the past, which is why she’s had to learn to say no from time to time – even to “fantastic” clients. These days, she tries to maintain a work-life balance, although it’s not always so easy for a freelancer.

“I still work every day, and I love it.”

Herba has been working as an illustrator for almost 20 years and finally feels that her hard work is paying off. She’s received recognition in her field. Her name has left an imprint, so to speak.

“I can now work with clients that I want to work with. I’m also much more confident nowadays and no longer worry about whether I’m good enough at my job.”

Her work speaks for itself, and Herba has an impressive clientele. It includes almost all major international newspapers, such as The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, Der Tagesspiegel, The Atlantic and Vanity Fair. And let’s not forget Google and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The list also includes around ten publishing houses, and twice as many books have been published.

“I like variety,” Herba says.

Picture books can take a year or two to complete, while editorial assignments need to be finished quickly.

“It’s so rewarding to work for a couple of days without any sleep and then be delighted with the end result.”

I believe our style evolves throughout our lives and changes as we change.

Feelings of uncertainty in her early career may have been fuelled by the fact that she has a degree in jewellery design and manufacture rather than one from an academic art school. She also spent five years studying art history at Wroclaw University.

Indeed, how many teens actually know what they want to do when they grow up?

“When I got my first commercial assignment, I was still very unsure of my abilities. After all, there are so many brilliant illustrators with diplomas and degrees.”

She now feels like she’s found her own style as an illustrator, that she’s “moving in a good and interesting direction”, even though the process is never fully finished.

“I believe our style evolves throughout our lives and changes as we change. I know this sounds a bit silly and romantic.”

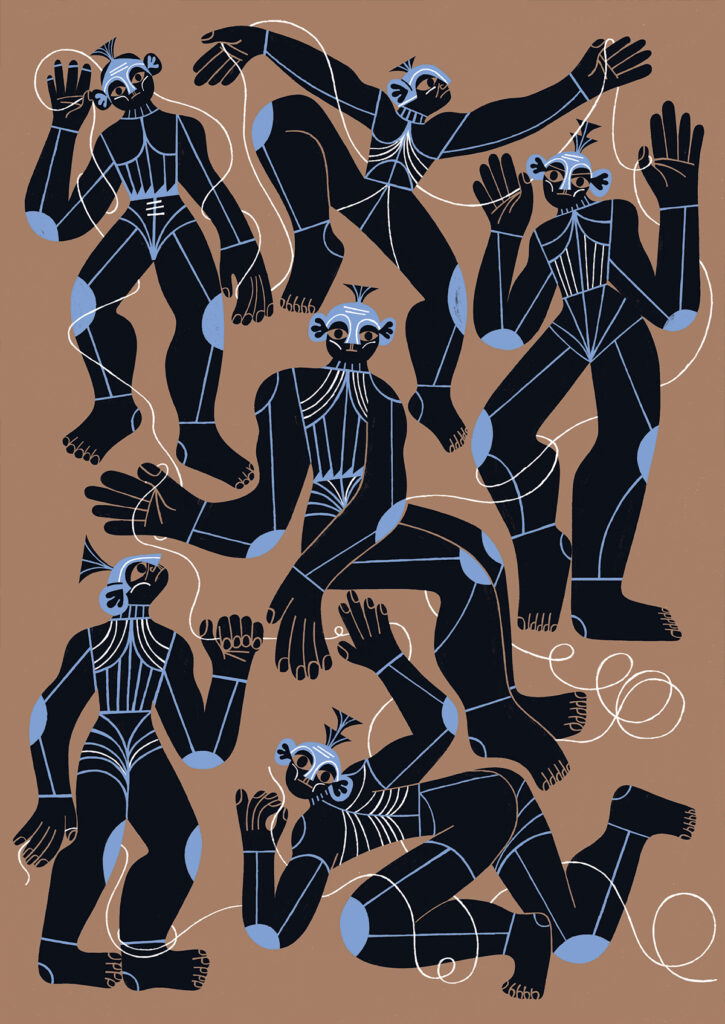

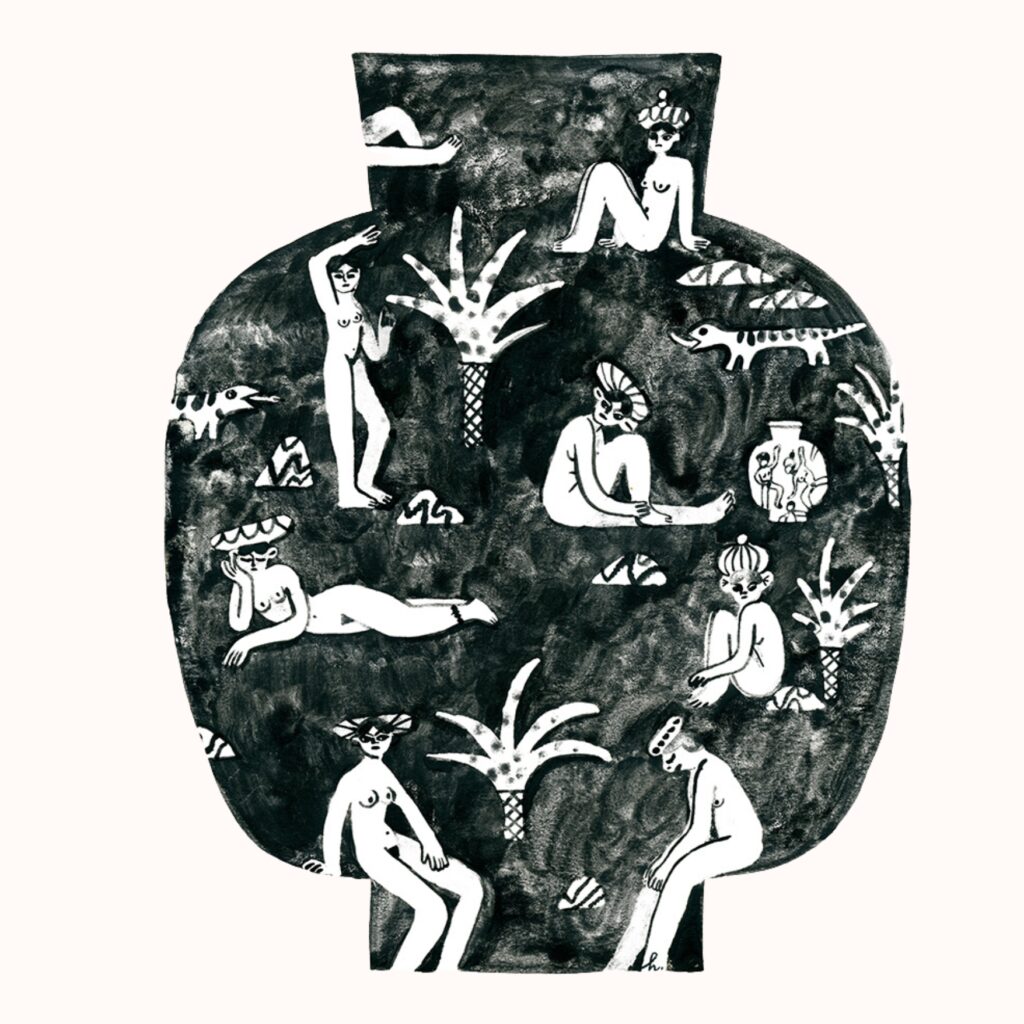

But is it silly and romantic, or enchanting and even dreadful? Herba’s work can be experienced in a multitude of ways. Often her illustrations, paintings and drawings lead the viewer into lush forests and mysterious gardens, where strange creatures of fascinating proportions roam. While her work is strongly influenced by early 20th century modern art, she combines her sources of inspiration in a refreshingly rich and original way.

A decade or so ago, Herba was enthralled by Cubism, and in particular by the works of Pablo Picasso from his Cubist period. “Like Picasso’s paintings”, her illustrations were often described. The name of Henri Matisse was also oftentimes mentioned in connection with her.

In the end, these sources of inspiration became a sort of trap, as she felt limited by the constraints of her own style.

“I’ve realised later on that I don’t have to stick to one particular technique or one particular way of drawing characters.”

I’ve realised later on that I don’t have to stick to one particular technique or one particular way of drawing characters.

For Herba, every character is a self-portrait in one way or another. She embraces romanticism once more, stating that her style is grounded in sincerity. “Sincerity is the foundation of style, if you really want to create art from the heart,” she says. A multitude of things contribute to it, of course – all of your experiences and encounters, all the films you’ve seen and books you’ve read, all the journeys and memories you’ve made.

“Please, you’re killing me,” Herba cries out. She laments the fact that she can’t rattle off a list of Finnish illustrators. She does name four, however: Tove Jansson (1914–2001), Ebba Masalin (1873–1942), Camilla Mickwitz (1937–1989) and Suvi Suitiala.

As a child, Tove Jansson’s The Dangerous Journey (1977) made a particularly lasting impact on her. She spent months immersed in the book, studying and drawing Jansson’s illustrations.

“I desperately wanted to learn to draw like her. Jansson’s ability to create characters was phenomenal.”She also highlights Masalin’s plant-themed illustrations with black backgrounds as well as Mickwitz’s psychedelia and the hilarious character of Jason. Among contemporary artists, Herba praises Suvi Suitiala, whose illustrations are characterised by vibrant colour palettes, strong shapes as well as textures. Like Herba, Suitiala has also worked for The New York Times.

Herba’s illustration style can be adapted to many different projects. Herba’s aim is to bring out the “deeper meaning of style”, as it’s not just a visual signature, but an expression of the author’s personality in a much broader sense. Style should never be a cage but rather an ever-evolving tool.

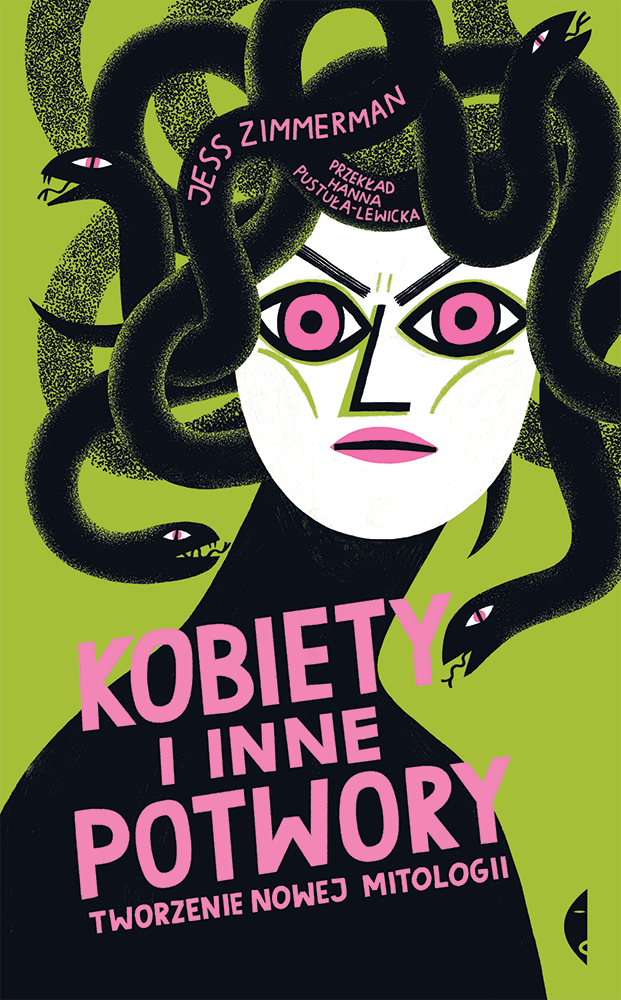

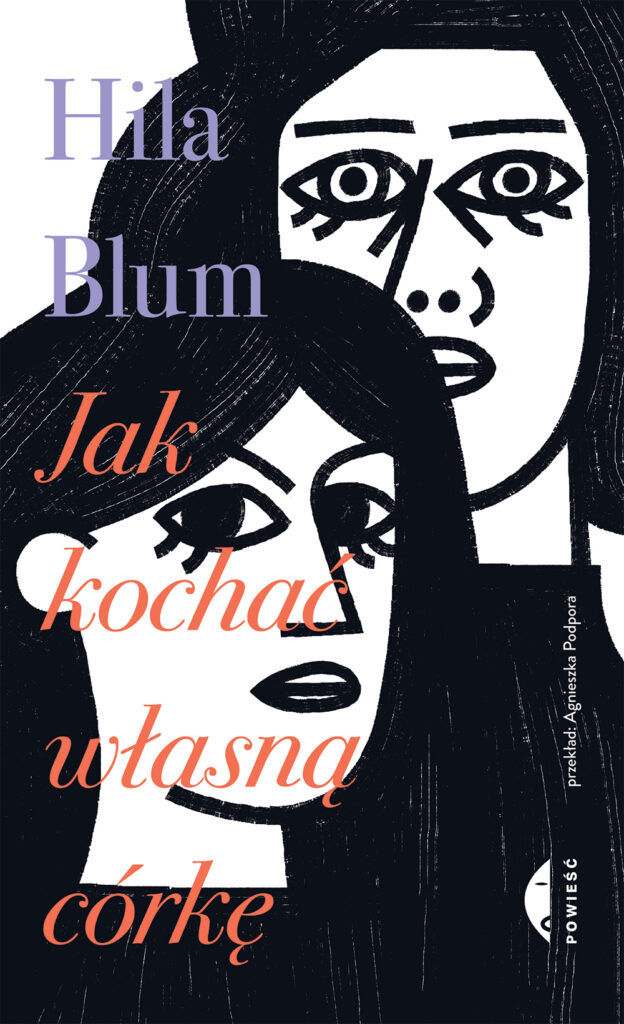

Herba gives an example of her own way of working: When designing a book cover, she naturally starts by reading the text first. Then she comes up with, say, three different ideas, from which she selects the one she thinks is the best. At this stage, she already knows what she wants to draw, but not yet how she wants to draw it. The final pieces are formed by experimenting with different techniques, colour palettes and so on.

“Personal styles can be incredibly flexible tools. Too many illustrators get trapped in their own visual form by always drawing similar characters and using the same colour palette.”

“That’s not necessarily a bad thing either”, Herba adds, but she’s interested in the process as a whole.

____________________

Published in Kuvittaja Magazine 2/25.